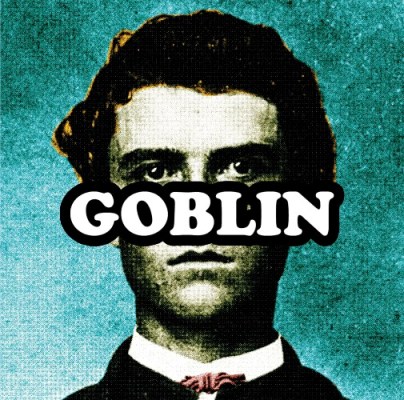

Tyler, the Creator, Bastard

XL Recordings

Perhaps the best thing about “Tyler, The Creator†Okonma’s Goblin is that he has mastered the art of intimacy. Throughout this nearly hour-and-a-half therapy session, he sounds as if he is speaking directly to you. However, therapy sessions usually last an hour. By stretching the listener’s patience to its breaking point, and offering modest emotional returns, he impresses with his self-absorption instead of his catharsis.

Tyler’s breakthrough arrives in the final track, “Golden,†when he announces “I’m not crazy.†In the first track, “Goblin,†he subtly broadcasts that he’s capable of change in spite of the worrisome obscenities that will follow. “I’m not a fucking rapist, or a serial killer. I lied,†he says to his “therapist,†which is actually his own voice modulated to a low growl. Speaking to his “conscience,†he adds, “They claim that shit I say is just wrong/ Like nobody has those really dark thoughts when alone.†He doesn’t spend much time bidding for the audience’s sympathy because no one wants a pity party. He knows that what we really want to hear are the vicarious thrills of calling someone nigga, a bitch, and a faggot; of raping and cannibalizing women; and of entertaining an interest in Nazism (though that last point is less pronounced here than on his debut solo album, 2010’s “freelease†Bastard).

Goblin’s wanton blasphemies have been debated ad nauseum in the press and on the Internet. Without excusing Tyler’s lyrics, it’s worth noting that the history of hip-hop is littered with examples of hate speech, from Brand Nubian’s “Punks Jump Up to Get Beat Down†(where Sadat X raps, “Fuck up a faggot/ Don’t understand their ways and I ain’t down with gaysâ€) to Gucci Mane’s The Return of Mr. Zone (on “Mouth Full of Golds†he warns, “I’ll rape you like Chester†the Molester). The mainstream rap industry’s bridge to international pop ubiquity was built literally and metaphorically on the backs of women, and patriarchal dominance is central to its success. Gays and lesbians play central behind-the-scenes roles as label executives, stylists, and publicists – Odd Future DJ Syd the Kyd, who recorded and mixed much of Goblin, is an out lesbian. Thematically, they mostly end up as collateral damage and reduced to metaphorical slurs (though women are often employed for pornographic girl-girl-guy fantasies).

The difference between Goblin and incendiary classics such as Ice Cube’s Death Certificate and the Geto Boys self-titled debut is that Tyler doesn’t aspire to black revolution or even a crude kind of cinema verité. Tyler’s Compton is an exurban dystopia, not N.W.A.’s capitol of gangland tragedy. He plays Xbox in a mancave full of wet socks; he flaunts his designer streetwear in Goblin’s CD booklet. With so many toys to play with, Tyler’s “Radicals†aspires to nothing more than to “kill people, buy shit, fuck school.†At several points he talks about masturbation, invoking himself as just another bored teenager jizzing to the tits-and-hipsters in Vice magazine. And in “Yonkers,†he pictures himself on “some pink Xanies/ And danced around the house in all-over pink panties.†He angrily refers to his missing father. He loves his mother, but admits he can’t relate to her.

In spite of his many cultural signifiers, Tyler complains loudly about being pigeonholed. “We don’t fuckin’ make horrorcore you fuckin’ idiots,†he announces at the end of “Sandwitches,†denying the legacy of RZA’s mid-90s Goth rap project the Gravediggaz. “Listen deeper to the music before you put it in a box.†Many reviewers have aptly compared Tyler’s image to the cynical and androgynous skate rats in the 1990s film Kids. Just like critics overstated that film’s “youth gone wild†revelations, some have tried to paint Tyler as a cipher for What’s Wrong with Today’s Generation. However, anyone who has run afoul of Internet trolls or scrolled the comments section on a Nahright.com blog post will find Tyler’s inflammatory language depressingly familiar.

Tyler’s production techniques seem inspired by the Neptunes’ cracked-out landscapes for Clipse’s Hell Hath No Fury, and the neo-soul erotica of Sa-Ra Creative Partners. On “Yonkers†he sequences an arrangement that sounds like a swinging guillotine, and he weaves a haunting synth-funk groove for the instrumental “Au79.†The jarring, primordial beats serve as backdrops for his psychotic ramblings. He has a magnetic basso voice, and he raps with a growling leer. He flips rhymes with the casualness of someone who has grown up with hip-hop all his life, and is all too comfortable in its netherworld of hardcore niggas and submissive bitches. It might be strange to older listeners who remember when hip-hop first reached critical mass in the late 80s (or, god forbid, when it first broke nationally in the early 80s), and don’t necessarily take its stereotypes for granted.

As a rapper, Tyler’s capable enough, but his technical skills pale in comparison to Eminem, whose serial killer schtick on The Marshall Mathers LP fomented the kind of indignant protests and amoral industry buzz that now surrounds Goblin. With so many precedents before him, it’s not easy for Tyler to shock listeners and precipitate what Jon Caramanica of the New York Times correctly labeled “culture wars for a generation that hasn’t previously experienced them, that didn’t realize culture wars were still a possibility.†By delivering his shocks early and often, Tyler wears down, upsets and eventually outrages his audience, conjuring an impressively discomforting anomie.

Goblin’s nadir and/or high point arrives during “Tron Cat,†when he raps about raping a “pregnant bitch.†(Several lines earlier in the song, he contradictorily claims, “I’m not a rapper, or a rapist, or a racist.â€) He claims himself “the blackest skinhead since India.Arie†and adds, “Said fuck coke so I snorted Hitler’s ashes.†And for extra thrills, he says you can catch him in the attic “taking photos of my dad’s dick.â€

But overall, Goblin is not a pleasurable listening experience. Some of the songs are truly awful, like the swag-rap roundelay “Bitch Suck Dick†with Odd Future compatriots Jasper Dolphin and Taco. (OFWGKTA’s guest appearances seem irrelevant here, save for a few inspired vocals by R&B singer Frank Ocean.) Other tracks aim closer to raw and unfettered anguish. Some of Tyler’s feelings are couched in the everyday hustle for celebrity, and of the predictable alienation that results when he finally achieves it. “Now you want to be nice because the labels want to sign me?†he asks on “Nightmare.†“Fuck that!†He rhymes about being stressed out and suicidal. He refers to himself as a goblin, a demon, a genie, and a unicorn.

On “Her,†Tyler obsesses over a next-door neighbor with heartbreaking sincerity, poking her on Facebook and gabbing with her on the phone and in video chats. “I know she’s who I’m thinking of,†he raps, adding that he wants to take her like a pirate. “Her name is my password.†It’s not enough to dispel Tyler’s Madonna/whore complex, but it marks halting progress. Unfortunately, Goblin isn’t a real-life therapy session, and the audience, not Tyler, foots the bill.

————

This is an extended version of a review originally written for Rhapsody.com.