Rap Is Not Pop: Kid Cudi, Eminem and the Perils of Addiction

This post is inspired by a commenter on my recent piece about Eminem and his album Recovery. “Somebody’s finally on the radio talking about NOT doing drugs. That’s a good thing,†wrote Halo in the comments section. “I know that it’s tough being clean and still keeping it real.â€

Why has there been so little hip-hop that addresses drug and alcohol addiction? It’s not as if rappers aren’t abusing drugs: The tabloids are filled with their exploits, whether it’s Lil Wayne serving time for drug possession, T.I. violating his probation over Ecstasy tablets and codeine syrup, or Gucci Mane reportedly heading to rehab. It appears that the days when it was only “cool†to smoke weed are a thing of the past. Yet those personal struggles rarely make it into the music.

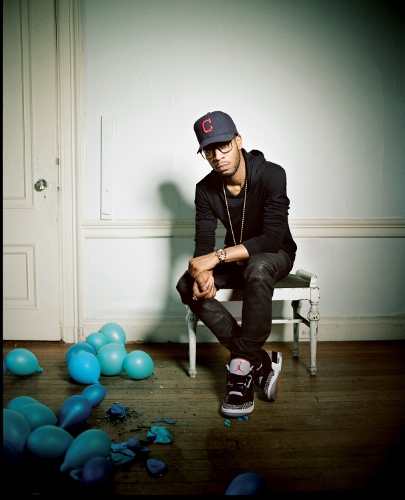

Kid Cudi’s new album, Man on the Moon II: The Legend of Mr. Rager, offers a striking counterpoint to Eminem’s Recovery. While Eminem related his drug problems like he was confessing at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, Kid Cudi hides his troubles within ramblings about the pressures of fame. He celebrates his love of herb on “Marijuana†– but marijuana’s not a drug, right? However, he doesn’t address his public struggle with cocaine, save for an audible snort during “All Along.†Man on the Moon II reflects the rap community’s general ambivalence towards party favors, and how overuse of them can destroy careers – and lives.

Rare are the examples of rappers who cop to drug problems. When Coolio emerged from WC and the Maad Circle to launch a solo career, he used his criminally-underrated 1993 single “County Line†to note that he lost years to crack addiction. And after earning a sordid reputation for being a coke fiend, Cage got clean, and has used subsequent albums like 2005’s Hell’s Winter and 2009’s Depart from Me as post-rehab therapy. These and songs by others like Fatlip (“What’s Up Fatlip?) and Tech N9ne (“T9Xâ€) fall into the realm of public confessionals.

Then there is Andre 3000, who admittedly wasted the success of OutKast’s 1994’s debut Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik on living the rap life – getting high and chasing girls – before experiencing a spiritual awakening. “In the Jacuzzi catching the Holy Ghost/ Making one woozy in the head and comatose,†he remembers on “Life in the Day of Benjamin Andre,†the closing track to OutKast’s Speakerboxxx/The Love Below. “I hadn’t smoked or took a shot of drank because I started off the second album on another note.†Andre made such a remarkable visual and musical transformation for OutKast’s second album, 1996’s ATLiens, from wearing a white robe and head scarf to reciting Nuwabian beliefs that the Egyptians were descended from aliens, that some fans speculated he was on drugs. On “Return of the ‘G’†from 1998’s Aquemini, Andre staunchly defended his new look: “Return of the gangsta/ Thanks ta/ Them n*ggas who get the wrong impression of expression/ Then the question is, ‘Big Boi, what’s up with Andre?/ Is he on coke?/ Is he on drugs?/ Is he gay?/ When y’all gon’ break up?’/ When y’all gon’ wake up/ N*gga I’m feeling better than ever/ What’s wrong with you?â€

Fans didn’t question Andre 3000 because he stopped getting high. They wondered why he changed. The hip-hop audience seems to loathe personal and artistic evolution unless it’s within a pop context of Bowie-esque visual and sonic transformation; OutKast’s mastery of that dynamic made it one of the past decade’s best-selling artists. But for those who don’t hold pop ambitions, staying the same appears to be the only recourse. On “Can It Be So Simple (Remix) from 1995’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx…, Raekwon rhymed, “Now I’m all about G notes/ No more time for weed mixed with coke/ I wash my mouth out with soap.†Of course, he spent much of his 2009 sequel Only Built 4 Cuban Link…Part II regressing into cocaine glory.

Another example of creative recidivism is Queensbridge rapper Prodigy. On Mobb Deep’s 1999 hit single “Quiet Storm,†he vowed, “I spent too many nights sniffin’ coke, gettin’ right/ Wastin’ my life/ Now I’m tryin’ to make things right.†Years later, he released the excellent Return of the Mac, and its centerpiece was “Mac 10 Handle.†“I sit alone in my dirty ass room staring at candles/ High on drugs,†he begins, interpolating a lyric from Geto Boys’ “My Mind Playing Tricks on Me.†Prodigy never says what type of drugs he’s on. But Alchemist’s sampling of Edwin Starr’s “Easin’ In,†which he turns into a mottled, bluesy refrain for Prodigy’s violent rant, leaves the impression that the rapper is all tweaked out.

“Mac 10 Handle†illustrates that, when it comes to exploring the depths of drug addiction, rappers tend to rely on our imaginations as a guide, while marking a path with breadcrumbs like dusty blues loops, downbeat and menacing keyboard sounds, and lyrical admissions of paranoia. These bleak arrangements are meant to contrast with the Ecstasy-popping adventures of Mack 10’s “Pop X,†Gucci Mane’s “Pillz†and D4L’s “Scotty.†Whereas one side highlights Ecstasy as a positive experience and frequent sex tool, the other hints at overuse, a burdensome monkey on the back.

Incredibly, despite all the recent headlines of arrests, real drug addiction remains taboo in hip-hop. Many of us remember the crack epidemic of the 80s and 90s and how it affected our communities. And so, despite the Ecstasy vogue, hip-hop fans don’t want to return to the wanton abandon of the disco era and Grandmaster Melle Mel’s “White Lines (Don’t Do It).†But what if that era has already reappeared, but we just don’t want to admit it? In a world that emphasizes mastery of your environment at all costs, copping to addiction signifies a loss of control and personal weakness.

Kid Cudi is often dismissed by critics as an electro-hop dandy, but he’s just as obsessed with dominance as the next rapper. So, for The Legend of Mr. Rager, he explained his personal troubles through a prism of the perils of fame and leading a revolution or “Revofev.†He unveils a new sound, too. Whereas Man on the Moon: The End of Day celebrated introspection as a psychedelic journey, complete with electro sounds and stories of mushroom-eating as foreplay (“Enter Galactic (Love Connection Part 1)â€); The Legend of Mr. Rager simmers with melodramatic strings, emo-ish ballads and cryptic lyrics like “All Along’s†“I’m addicted to highs/ Would you like to know why? … I don’t want what I need/ What I need hates me.â€

Narcotic addiction isn’t just an occupational hazard for celebrities both real and pseudo, but a problem that affects wide swaths of the population. Perhaps that’s why Eminem’s Recovery may be less musically sophisticated than The Legend of Mr. Rager, but it is more honest. “You’re lying to yourself,†says Eminem on “Talkin’ 2 Myself.†He could be speaking for a generation of MCs dabbling with hard drugs yet are afraid to look in the mirror.

—————————

This essay was posted November 9 on the Rhapsody SoundBoard blog. I wrote it for my Rap Is Not Pop column.

Photo by Pamela Littky.

Excellent